Medical Device

Req 47? One click.

ISO 13485, EU MDR, FDA 21 CFR 820. Design controls through post-market surveillance. When the auditor asks to see requirement 47, you click once.

The Audit That Exposed Everything

The Notified Body auditor asked one question: "Show me how requirement 47 traces to verification."

The quality manager pulled up the requirements document—a Word file with 312 requirements numbered sequentially. Requirement 47: "The device shall deliver fluid at rates between 0.1 and 999.9 mL/hr with accuracy of ±5%." Simple enough. Now find the trace.

The trace matrix lived in Excel. Scroll to row 47. It said "REQ-047 → DV-103 → VER-047." But DV-103 was a design output reference to a CAD drawing. Where was VER-047? The matrix didn't say. Someone opened the verification folder in SharePoint. Hundreds of protocols. VER-047... search... nothing. Check naming convention. Maybe it was VP-047. No. Maybe 047 was the requirement number but the protocol had a different sequence. Open several protocols, scan headers.

Forty-five minutes into the audit, still searching. The auditor wrote the finding: "Traceability between design requirements and verification is not adequately maintained."

That finding cascaded. No traceability means no design control. No design control under MDR means you cannot demonstrate the device meets essential requirements. Major nonconformance. Certification at risk. Eight months of remediation ahead—rebuilding the trace matrix, re-executing verification to link properly, re-reviewing design outputs to ensure coverage.

The irony: the verification existed. Someone had written a protocol, executed it, documented that the pump achieved ±2.1% accuracy across the rate range. The evidence was there. The chain to find it was broken.

The Document Management Trap

Most medical device companies run design controls as enhanced document management. Requirements live in Word. Design outputs live in CAD systems and engineering documents. Verification protocols live in Quality's folder structure. Test results live in lab systems or spreadsheets. Risk analysis lives in Excel with severity and occurrence ratings.

The trace matrix is the desperate attempt to connect these islands. An overworked QA engineer maintains it—usually between audits, frantically, when everyone remembers it matters. Every time a requirement changes, someone must update the Word document, find and update all downstream references, modify the trace matrix to reflect the new state. Every "someone must remember" is a failure point.

The matrix itself is metadata about documents, not the documents themselves. When it says "REQ-047 → VER-047 → PASS," you still have to find VER-047 to verify the claim. If the naming convention drifted, if someone saved to the wrong folder, if there was a versioning issue—the matrix lies. It says traceability exists when the actual chain is broken.

This gets worse over time. Design changes accumulate. Requirements evolve. New team members don't know historical context. The matrix becomes increasingly fictional—a document that must be true for compliance, maintained to look true, but never actually verified as true until an auditor tries to follow a chain.

Traceability as Structure, Not Artifact

Seal inverts the traditional approach. Traceability isn't a matrix you maintain after the fact. It's how work gets done in the first place.

When you create a verification protocol, you don't file it in a folder. You create it linked to the requirement it tests. The link isn't a cell reference—it's a database relationship. The protocol knows which requirement it verifies. The requirement knows which protocols verify it.

When you record test results, they attach to the protocol. Pass or fail, with data, linked to the execution. The requirement now has a complete chain: itself → the protocol that tests it → the results that prove it.

Design outputs work the same way. A CAD drawing isn't a file somewhere—it's a record linked to the requirements it implements. When you update the drawing, the version history maintains the link. When someone asks "which requirements does this drawing address?", the system answers instantly.

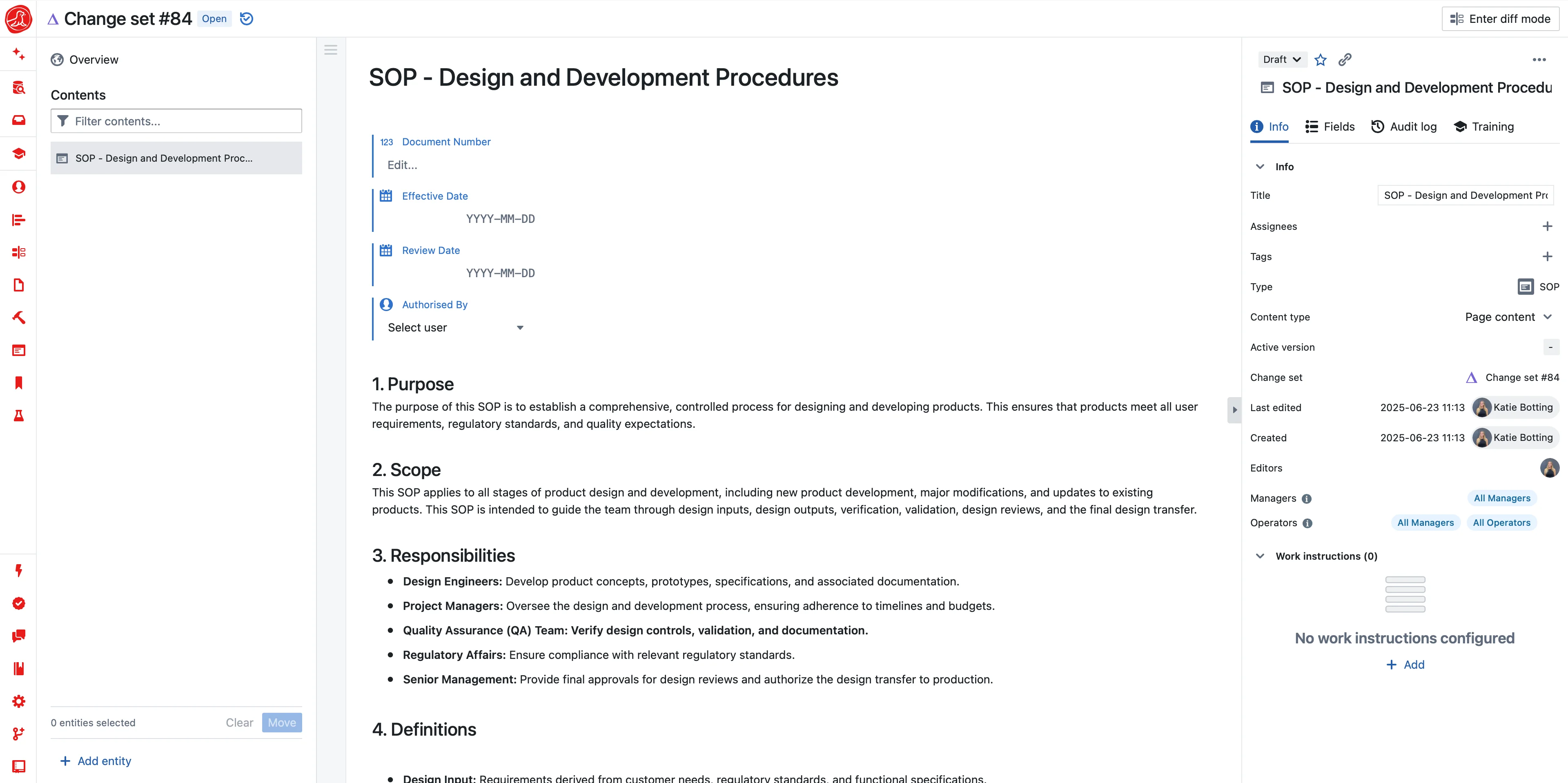

Click requirement 47. See its rationale (why this requirement exists), its source (user need, regulatory standard, risk control), the design reviews that evaluated it. Click "traces forward" and see the design output, the verification protocol, the test results with actual data. Click "traces to risk" and see which hazards this requirement controls, what residual risk remains.

The auditor's question—"show me how requirement 47 traces to verification"—is one click. Not because someone maintained a matrix, but because the work was done in a structure that captures traceability as it happens.

Risk Management That Breathes

ISO 14971 requires a risk management process: identify hazards, analyze hazardous situations, estimate risk, implement controls, evaluate residual risk. Most organizations treat this as a documentation exercise. Build the Risk Management File during development. Get it approved. Archive it. Update reluctantly when auditors complain.

The problem: risk isn't static. The hazards you identified during development were your best guess before anyone used the device. Field experience reveals hazards you didn't anticipate—use errors that seemed implausible, failure modes that weren't obvious, environmental conditions you didn't consider. A Risk Management File frozen at approval becomes increasingly fictional.

Seal treats risk as live analysis, not archived documentation. Hazards are records, not rows in a spreadsheet. Each hazard links to hazardous situations—the sequence of events that leads from hazard to harm. Each situation links to potential harms with probability and severity. Risk controls link to the hazards they address and to verification that proves they work.

When a complaint suggests a new hazard, add it. The system shows what else is affected—which requirements address it, which controls might mitigate it, where in the design the hazard manifests. When design changes introduce new failure modes, the risk analysis updates. When you need the current risk picture for a design review, generate it from live data.

The benefit-risk determination MDR requires becomes tractable. Clinical benefits documented with evidence. Risks characterized with current analysis. The comparison traceable to source data. When benefit-risk needs updating—new clinical data, new adverse events, new intended use—you update the sources and regenerate. The determination stays current because the underlying analysis stays current.

Technical Documentation Without Panic

Three weeks before submission, most companies panic. The Technical Documentation needs to be assembled—Annex II requires everything from device description to clinical evaluation to post-market surveillance plan. Someone pulls documents from SharePoint, shared drives, email threads. Someone else tries to figure out which version is current. The clinical evaluation references risk analysis from six months ago. The GSPR compliance matrix was last updated before the most recent design change. Inconsistencies surface. People scramble to fix them while creating new ones.

This isn't preparation—it's reconstruction. And it's instantly outdated because development continued while you assembled. The document you submit is already behind the actual state of the device.

Seal maintains Technical Documentation as views of live data. Annex II sections don't pull from scattered folders—they render from system records. Device description comes from your master record. Design information comes from your DHF. GSPR compliance comes from requirement-to-regulation mapping. Risk analysis comes from your live risk management. Clinical evaluation comes from your CER with linked literature and post-market data.

Generate Technical Documentation and you're rendering current state, not assembling historical snapshots. The Notified Body asks for an update six months later? Generate again. Same process, current data. The representation is always consistent because it's always derived from the same underlying truth.

Different markets need different formats. EU MDR Annex II structure. FDA 510(k) format. Health Canada requirements. The underlying data is the same—device description, risk analysis, clinical evidence, quality system documentation. The presentation differs. One source of truth serves multiple regulatory submissions without multiplication of effort or consistency risks.

Post-Market Surveillance That Detects

PMS under MDR isn't passive collection. It's active surveillance that must proactively gather and analyze data to detect problems before they become incidents. The PMSP must describe how you'll do this. The PSUR must demonstrate you did it.

Most organizations struggle because post-market data arrives from everywhere. Complaints come through customer service in a ticketing system. Vigilance reports route through regulatory affairs in emails. Literature monitoring happens in medical affairs spreadsheets. Registry data (when available) comes from clinical. PMCF studies run through R&D. Each stream has its own format, its own system, its own people. Detecting patterns across streams requires manual aggregation that happens too rarely and too slowly.

Seal consolidates sources into unified surveillance. Complaints enter as structured data—product identifier, event description, patient outcome, investigation findings. Not free text in a ticket, but queryable data that enables trend analysis without someone reading every complaint. Literature monitoring flags relevant publications automatically. Registry data imports with standard metrics. PMCF results integrate as they arrive.

The system analyzes continuously. When alarm-related complaints exceed historical baseline, the system surfaces it—not because someone noticed while preparing a quarterly report, but because statistical detection runs against live data. When a new publication reports an unexpected failure mode, it routes to the right people with the relevant device context.

When a signal crosses threshold, action follows. The complaint trending that triggered concern. The affected products with lot numbers and distribution records. The risk analysis that now needs updating. FSCA documentation generates pre-populated with what you know. You respond to signals, not to audit findings about signals you should have caught.

AI That Closes Gaps

Setting up design controls traditionally means months of template creation—requirements formats, risk analysis structures, DHF organization, traceability matrices. AI changes the economics completely.

Describe your device: "Class IIb implantable cardiac monitor with wireless telemetry." AI generates the design control framework—requirement categories mapped to EU MDR essential requirements, risk analysis structure following ISO 14971, DHF organization matching Annex II. You review and refine rather than building from scratch.

Risk analysis accelerates dramatically. AI suggests hazards based on device type and intended use. "Implantable devices with wireless communication typically face these hazard categories." You evaluate relevance, add device-specific hazards, complete the analysis. The starting point isn't blank—it's informed by regulatory expectations and industry patterns.

Every AI proposal is transparent. When AI suggests a GSPR mapping or hazard category, you see exactly what it's proposing. Design control records go through your standard review. Risk analysis requires human evaluation. AI accelerates the work; your team makes the decisions.

And AI works throughout operations. Writing requirements—AI flags ambiguity and suggests measurable criteria. Building traceability—AI scans for gaps continuously. "Design input DI-047 has no linked verification." Compiling Technical Documentation—AI generates Annex II structure from linked records. Preparing for audit—AI identifies documentation gaps before auditors arrive.

The DHF that took months to compile generates in seconds. The gaps that auditors found during the audit surface during development. The Technical Documentation that was always slightly stale stays current because it derives from live data.

The Next Audit

Same Notified Body. Same auditor. The question comes again: "Show me how requirement 47 traces to verification."

One click. The requirement appears with its design rationale—why the flow rate accuracy matters for the intended use. Click through: the design output specifying pump mechanism, the verification protocol defining test method, the results showing ±2.1% accuracy across the rate range with raw data attached. The design review that evaluated it. The risk controls it satisfies—HAZ-023 (incorrect dosing) mitigated by this accuracy requirement. The GSPR mapping to essential requirement 11.1.

"Post-market data for this requirement?" The surveillance dashboard filtered to flow-rate-related complaints. Trend line within normal variation. No signals detected. Three complaints investigated, root causes identified, none related to pump mechanism.

"Technical Documentation?" Generate. Annex II structure populates. 2,400 pages rendered in thirty seconds. Every section current. Every claim traceable to source.

"Risk analysis for the hazard we discussed last time?" Current state with the new hazard added after last audit's discussion. Analyzed, controlled, verified. Residual risk acceptable with documented rationale.

The auditor nods. Moves to the next topic.

No finding.

Getting Started

You're probably running design controls across Word documents, Excel matrices, and SharePoint folders. The fix isn't burning it all down—it's migrating methodically.

Start with a single device in development. Import existing requirements. Define the trace structure going forward. As you do new work—verification, design reviews, risk updates—do it in the structured system. Legacy content stays where it is; new work builds structure.

By the time that device reaches submission, you've learned the system through real work. The next device starts structured from day one. The trace matrix that used to take weeks to build never needs building—it exists because work happened.

Device companies that tried to migrate everything at once burned months and frustrated teams. Device companies that started with new work and migrated incrementally were operational in weeks.

Capabilities