Design Controls

Gaps found before audits. Not after.

The traceability matrix showed Input → Output → Verification for every requirement except one. Class I recall followed. Live traceability that exposes gaps before auditors do.

The Requirement Nobody Verified

510(k) cleared in 90 days. Six months later, a nurse called: the device was too hard to activate. Her patient's hand strength couldn't generate the required force. The patient was elderly, arthritic. The device was designed by engineers with healthy hands who never considered this use case.

The design input was there, buried in section 4.3.2 of the requirements document: "Activation force shall not exceed 2N." Copied from a predicate device. Nobody questioned whether 2N was the right number. Nobody built a test for it. The traceability matrix showed Input → Output → Verification for every other requirement. This one had a gap—a blank cell that nobody noticed until the FDA asked about it.

"How did you verify this requirement was met?" Silence. The verification protocol tested nineteen requirements. This one wasn't included. Someone assumed it would be obvious. Someone else assumed engineering had covered it. Nobody actually verified.

Class I recall. Public notification. Design modification. Resubmission. The gap cost eighteen months and a reputation.

The Documentation Trap

Most companies treat design controls as a documentation exercise. Requirements go in a Word document. Design outputs go in another Word document. A traceability matrix in Excel links them together—manually updated when someone remembers. Verification protocols are written, executed, and filed. The Design History File is assembled before audits by someone who wasn't involved in the development, pulling documents from shared drives and hoping nothing is missing.

This approach creates the illusion of control. Documents exist. Signatures exist. But the connections are fragile. When requirements change, does someone update the traceability matrix? When verification protocols are written, does anyone check that every requirement has a corresponding test? When the DHF is compiled, does anyone verify it's complete?

The gaps aren't visible until an auditor walks the matrix. By then, it's too late.

Living Traceability

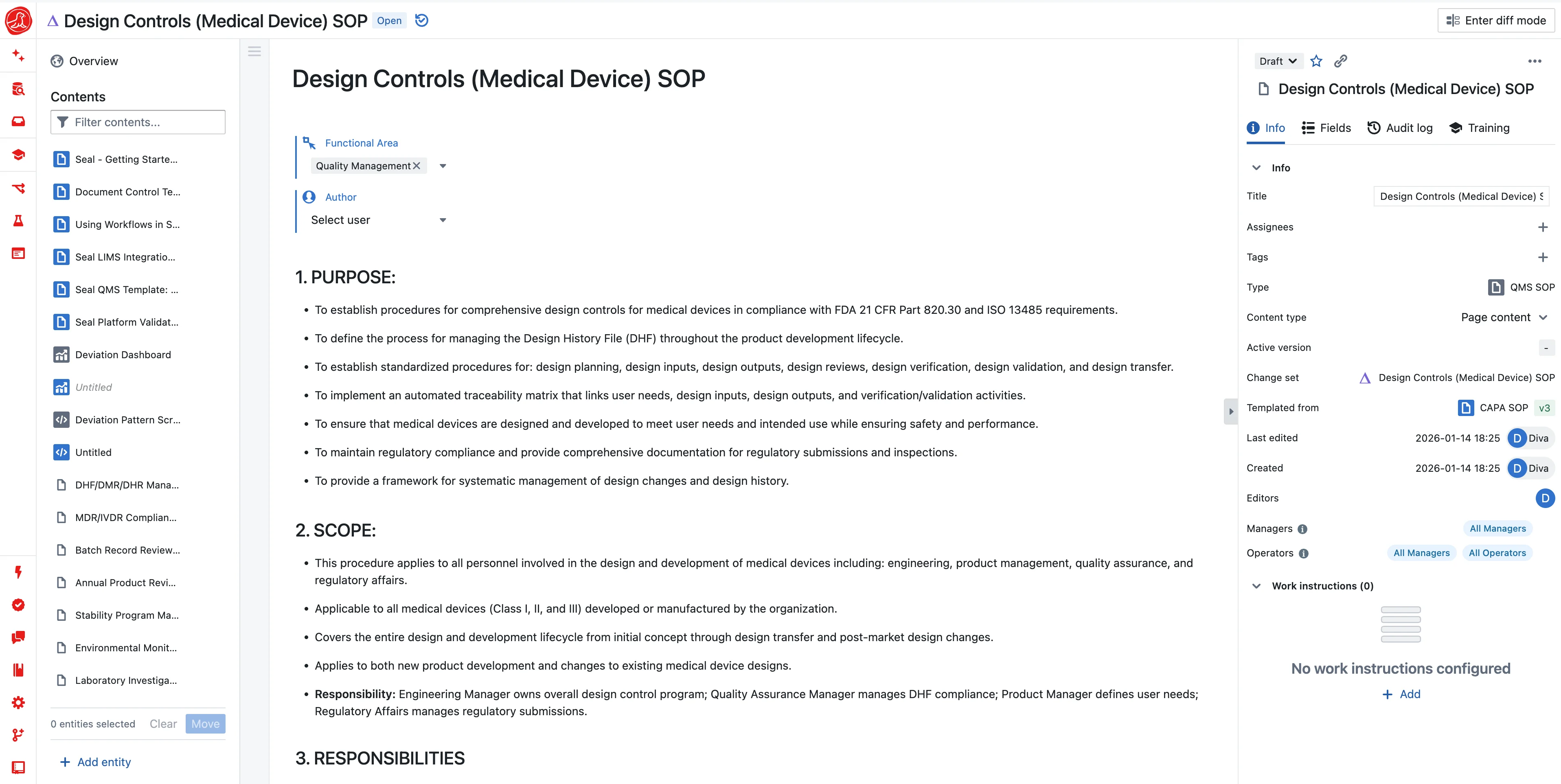

Seal makes design controls a living system where gaps become visible the moment they're created.

When you create a design input, it exists as a record in the system—not a line in a document. When you create a design output, you link it to the inputs it addresses. The system knows which inputs have outputs and which don't. When you create a verification test, you link it to the outputs it verifies. The system knows which outputs have verification and which don't.

The traceability matrix isn't a spreadsheet someone maintains. It's a view computed from actual relationships. When an input has no output, the matrix shows a gap. When an output has no verification, the matrix shows a gap. You see the gap immediately, not when the auditor asks about it.

When requirements change—and they always change—the system propagates the impact. A changed input flags its linked outputs for review. Changed outputs flag their verification tests for reassessment. The traceability doesn't break silently; it highlights what needs attention.

Inputs: Where Everything Begins

Design inputs are the foundation. Everything else traces back to them. If your inputs are wrong, your outputs will be wrong. If your inputs are incomplete, your device will have gaps.

Inputs come from multiple sources. User needs define what problems the device solves and for whom. Clinical requirements specify outcomes, populations, and indications. Regulatory requirements flow from applicable standards—IEC 60601 for electrical safety, ISO 10993 for biocompatibility, specific FDA guidances for your device type. Risk inputs emerge from hazard analysis—the design must mitigate identified risks.

Each input should be specific and measurable. "Easy to use" isn't a design input. "Activation force shall not exceed 2N" is a design input—though you'd better verify that 2N is actually appropriate for your user population. Each input should trace to a source—why is this a requirement? Each input needs a corresponding output and verification.

Outputs: The Actual Design

Design outputs are what you actually designed. Specifications define what the device must do. Drawings define physical characteristics. Software architecture defines computational behavior. Manufacturing procedures define how it's built.

Each output addresses one or more inputs. The traceability should be explicit—this specification exists because of that requirement. When an output doesn't trace to an input, you have a question: why does this exist? When an input doesn't trace to an output, you have a gap: how is this requirement addressed?

Output documents are controlled—versioned, approved, change-managed. When an output changes, its verification needs reassessment. When an output is approved, it's ready for verification.

Verification and Validation

Verification answers: do outputs meet inputs? You specified a 2N activation force. Does the device actually require less than 2N? You measure, you document, you conclude. Verification is objective evidence that the design output meets the design input.

Validation answers: does the device meet user needs? You can verify every specification and still fail validation if your specifications were wrong. Verification tests what you designed. Validation tests whether what you designed is actually what users need.

The distinction matters. You can have a perfectly verified device that fails validation because you didn't understand your users. The nurse's patient couldn't activate the device not because it failed verification—it met the 2N spec—but because 2N was too much force for elderly arthritic hands. The verification passed. The validation would have caught this if anyone had tested with representative users.

Design Reviews

Design reviews are cross-functional checkpoints. Engineering presents design status. Quality reviews documentation completeness. Regulatory assesses compliance. Manufacturing evaluates producibility. The review isn't a rubber stamp—it's a critical evaluation of whether the design is ready to proceed.

Each review has defined criteria. What should be complete at this stage? Are design inputs finalized? Are outputs documented? Are verifications planned? The review evaluates against criteria and documents findings.

Action items emerge from reviews. Gaps need closure. Questions need answers. The review doesn't close until action items are resolved. In Seal, action items link to the review, have owners and due dates, and track to completion. Reviews can't close with open items.

The Design History File

The DHF is the complete record of the design process—inputs, outputs, reviews, verifications, validations, changes. For a 510(k), it's the evidence supporting your submission. For an audit, it's the story of how you designed this device.

In most companies, the DHF is assembled before audits. Someone pulls documents from various locations, checks them against a DHF index, and assembles a package. Documents are missing. Versions don't match. Signatures are illegible. The assembly takes days and the result is uncertain.

In Seal, the DHF compiles automatically. Design inputs are in the DHF because they were created in the system. Design outputs are in the DHF because they're linked to inputs. Verification results are in the DHF because they're linked to outputs. Reviews and their action items are in the DHF. Changes and their approvals are in the DHF.

The DHF is always current because it's generated from live data, not assembled from archives. When an auditor asks to see the DHF, you show them—completely, accurately, immediately. When you prepare a 510(k), the design control evidence is ready because you've been maintaining it all along.

Design Changes

Designs change. User feedback reveals gaps. Testing discovers issues. Manufacturing identifies producibility problems. Regulatory requirements evolve. Changes are normal. Uncontrolled changes are dangerous.

Every design change follows design control. What inputs are affected? What outputs need revision? What verifications need re-execution? What validations need reassessment? The change doesn't just update a document—it updates the entire traceability chain.

In Seal, design changes link to the design records they affect. Impact assessment identifies downstream effects automatically. Changed outputs trigger verification reassessment. The system maintains traceability through changes, not despite them.

AI that builds your design control system

Setting up design controls traditionally means defining requirement categories, traceability structures, V&V templates, DHF organization—months of configuration for complex devices. AI compresses this.

Describe what you need: "We're developing a Class II cardiovascular device. We need design controls per FDA 21 CFR 820.30 with traceability from user needs through verification." AI generates the configuration—input categories for user needs, clinical requirements, and regulatory standards; output types for specifications and drawings; V&V templates; DHF structure following industry practice. You review and refine.

Requirement structures build from your inputs. "Our device must meet IEC 60601-1, IEC 60601-1-2 EMC requirements, and ISO 10993 biocompatibility." AI generates design inputs from applicable standards with appropriate verification approaches suggested.

Every AI proposal is transparent. Configuration changes go through your approval process. AI accelerates setup; your team controls the design.

And AI works throughout development. Writing requirements—AI suggests specificity improvements. "This requirement isn't measurable; consider adding acceptance criteria." Building traceability—AI continuously scans for gaps. "Design input DI-047 has no linked output." Preparing the DHF—AI compiles from linked records and flags incomplete sections before you need it for submission.

The Gap That Isn't There

The auditor asks about activation force. You show them the design input, linked to user research documenting the target population's hand strength. You show them the design output, the specification that translates user needs into measurable criteria. You show them the verification protocol, the test method, the results, the conclusion. The traceability is complete because the system wouldn't let you proceed with a gap.

The requirement nobody verified? That's no longer possible. The system makes gaps visible the moment they're created. You fix them during development, not during a recall.

Capabilities