Electronic Lab Notebook

Capture. Connect. Discover.

Turn experiments into structured data AI can actually use.

Your lab notebooks are black holes.

Every day, your scientists generate insights that could accelerate your pipeline. Every day, those insights disappear into paper notebooks, personal spreadsheets, and email threads. Scientists spend 20% of their time searching for information that already exists somewhere. When someone leaves, their knowledge leaves with them—and replacing a senior scientist's institutional knowledge takes years, if it's even possible. When you need to reproduce an experiment, you can't find the details. When regulators ask for data, you spend weeks assembling it from scattered sources.

The paper notebook was designed for a solo scientist in 1850. You're running a modern R&D organization with dozens or hundreds of scientists generating thousands of experiments per year. The tools should have evolved, but for most organizations they haven't.

The template trap

Modern ELNs promise structured data capture through templates. But this promise hides a fundamental trap: rigidity. These templates are static and monolithic, enforcing a single, inflexible way of working.

A template built for one process gets stretched and abused for the next, becoming a Frankenstein's monster of optional fields and confusing variations. Scientists face an impossible choice: either pollute the system with unstructured data in a template that doesn't fit, or create endless one-off variations that fracture context across dozens of templates.

The first path destroys searchability by reverting to prose. The second makes comparison impossible. Both paths make your data unusable—trapped in document-based formats, impossible to query, and worthless for training AI.

Scientists hate these systems because they're clunky. Managers hate them because data is still unstructured. IT hates them because they're yet another silo. The fundamental problem is that most ELNs digitize the notebook instead of the science.

Experiments are structured data

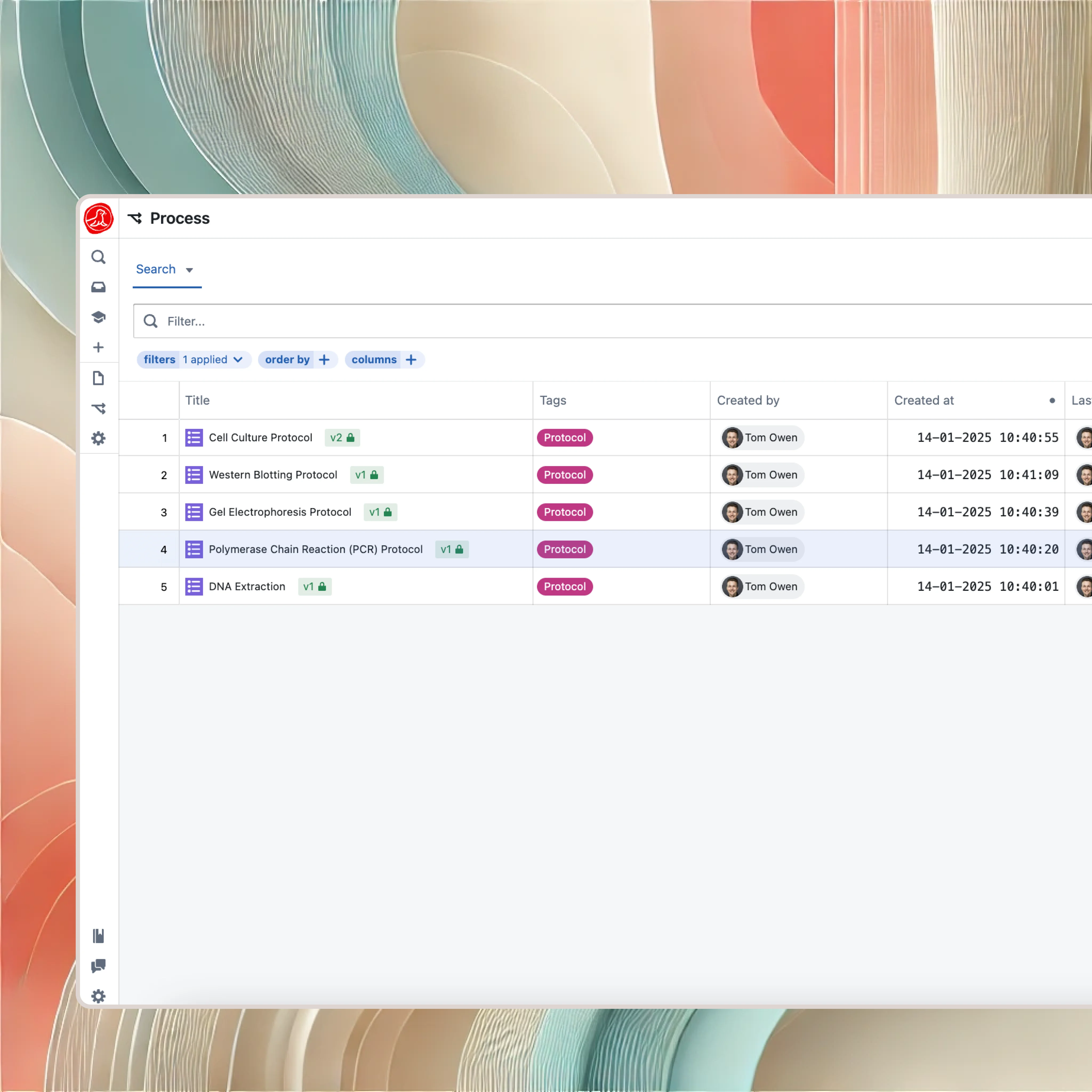

The Seal approach is different. An experiment in Seal isn't a blank page—it's an instance of a protocol.

When you define a protocol for PCR amplification, you specify what parameters matter: template concentration, primer sequences, annealing temperature, cycle count. When a scientist runs an experiment using that protocol, they fill in the specific values. The core structure is enforced, ensuring key parameters are always captured. But this is R&D, not manufacturing. Scientists can add steps, change parameters, and note observations freely. The structure captures what matters; the flexibility allows discovery.

This structure is what makes your science searchable. "Find all PCR experiments where cycle count exceeded 30" is a two-second query, not a two-week project of reading through notebooks. "Show me every experiment that used reagent lot X" is instant. "Compare the yield across all runs of protocol Y" generates a chart automatically.

Everything is connected

Your ELN shouldn't be an island. In Seal, experiments link directly to the real objects they reference.

Samples are real objects in the system. When your experiment uses a sample, you link to its record. Click through to see its full lineage—where it came from, what it's been through, where its derivatives ended up. Equipment is integrated the same way. Don't type "Centrifuge 3" as text; link to the equipment record. See its calibration status instantly. Know whether it was qualified when you ran your experiment.

Reagents and materials are tracked at the lot level. Link to the specific lot of antibody you used. If that lot is recalled later, you know exactly which experiments are affected in seconds, not days. If an experiment fails and you suspect the reagent, you can find every other experiment that used that same lot and see if they failed too.

This connectivity is what transforms an ELN from a documentation system into a knowledge system. The data doesn't just exist; it relates to everything else.

Collaboration is built in

Science is a team sport, but most ELNs treat scientists as isolated individuals writing in private notebooks that occasionally get shared.

Seal builds collaboration into the core workflow. Witnessing is one click—request a colleague to review and sign off on a critical step, and they get notified immediately. Their signature locks that portion of the record for IP purposes, with the timestamp providing legal defensibility.

Project sharing works the way scientists actually work. Define a project, add team members with appropriate access levels, and everyone can see and build on each other's experiments. Access controls are granular—some team members can edit, others can only view, and sensitive experiments can be restricted to specific individuals.

Real-time notifications keep teams synchronized. When someone completes an experiment that your work depends on, you know immediately. When a reagent lot you've been using gets flagged, everyone who used it gets alerted.

From R&D to QC

The biggest friction in biotech is tech transfer—moving a method from R&D to Quality Control. In traditional systems, this means copying information from notebooks to Word documents to QC SOPs to LIMS configurations. Every copy is an opportunity for error. Every translation loses context.

In Seal, the ELN protocol is the draft for the QC method. You develop the method in the ELN with full flexibility to iterate. When it's ready, you lock it down as a controlled QC method with specifications and acceptance criteria. Then it executes in the LIMS with full compliance controls.

Same platform. Same data structure. No copy-paste errors. The method that worked in development is exactly the method that runs in QC, because it's literally the same object in the system with different permission levels.

Searchability and reproducibility

The scientific method depends on reproducibility, but reproducibility depends on capturing enough detail to reproduce. Paper notebooks fail here because they capture what scientists remember to write down, not what actually matters. Electronic notebooks that are just text editors fail for the same reason.

Seal's structured approach means the system prompts for critical parameters. If your PCR protocol requires cycle count and annealing temperature, every experiment instance captures those values. The data that matters for reproducibility is captured by design, not by luck.

Search goes beyond keywords to structured queries. Find experiments by parameter ranges, by outcome, by the materials used, by who ran them, by date. Combine criteria: "all PCR experiments by Dr. Chen in Q3 where yield was below 50%." Export the results to analyze patterns.

When you need to reproduce an experiment, you have everything: the exact protocol version, the specific reagent lots, the equipment used, the environmental conditions, the raw data, and the scientist's observations. Reproduction becomes possible because the information was captured in a way that supports it.

The knowledge that stays

When a senior scientist leaves, what happens to their decade of expertise? In most organizations, it walks out the door. Their notebooks sit in a cabinet, technically accessible but practically useless—you'd have to read years of handwriting to extract the insights.

In Seal, their experiments remain fully searchable, fully connected, fully useful. The protocols they developed continue to be used. The patterns they discovered are encoded in the data structure. The knowledge they generated becomes organizational knowledge rather than personal knowledge.

This is the difference between a documentation system and a knowledge system. Documentation records what happened. Knowledge systems make what happened useful for what happens next.

AI That Builds Your Lab

Setting up an ELN traditionally means weeks of protocol creation—defining fields, setting up calculations, building templates for every assay type. AI changes this completely.

Describe what you need: "Create a protocol for ELISA with standard curve, sample dilutions, plate layout, and automated concentration calculation." AI generates the complete protocol—structured fields, embedded calculations, result formatting. Scientists review and refine rather than building from scratch.

Protocol libraries populate in days instead of months. "We run PCR, western blots, cell culture, and transfections. Create protocols for each." AI generates templates based on standard methods, then you customize for your specific workflows. The ELN that used to require a dedicated administrator is configured by scientists in plain language.

Every AI proposal is reviewable. When AI generates a protocol, you see exactly what it created—every field, every calculation, every validation rule. You edit, refine, approve. New protocols go through your standard review process before becoming available. AI accelerates creation; scientists control the science.

And AI works within every experiment. Starting a new run? AI suggests parameters based on what worked before. Entering results? AI flags anomalies against historical patterns. Analyzing data? AI identifies correlations across your experiment history—which conditions correlate with success, which combinations fail.

Literature connection closes the loop. AI surfaces relevant publications and similar experiments from your organization. What's been tried before? What worked? The context that accelerates discovery, delivered as you work.

This is what structured data enables. The AI that configured your protocols now accelerates every experiment within them.

Getting Started Without Disruption

You've probably seen ELN implementations fail. Six months of configuration, scientists forced into rigid templates, adoption that never happens because the system fights how people actually work. That's not how this works.

Start with one team, one assay type. Scientists describe their current workflow in plain language. AI generates the protocol structure. They run experiments for a week, refine what doesn't fit, and the protocol evolves. No consultants. No months of template design. Within days, you have a working protocol that captures what matters while letting scientists do their work.

Expand from there. The team that started shares their protocols with the next team. Common elements become library protocols. Variations become linked protocols that inherit the base structure. The ELN grows organically from actual use rather than top-down mandates.

Import historical data when it makes sense. That spreadsheet of experiments from last year? Import it as structured data. Those paper notebooks from the senior scientist who left? Scan them as attachments to experiments, searchable by date and project. You're not starting from zero—you're building on what exists.

The scientists who hated their last ELN will use this one. Not because you mandate it, but because finding that experiment from six months ago takes seconds instead of hours. Because they can actually see what their colleague tried before. Because the system helps them do science instead of fighting them.

Capabilities