Process Validation

Qualify. Monitor. Know.

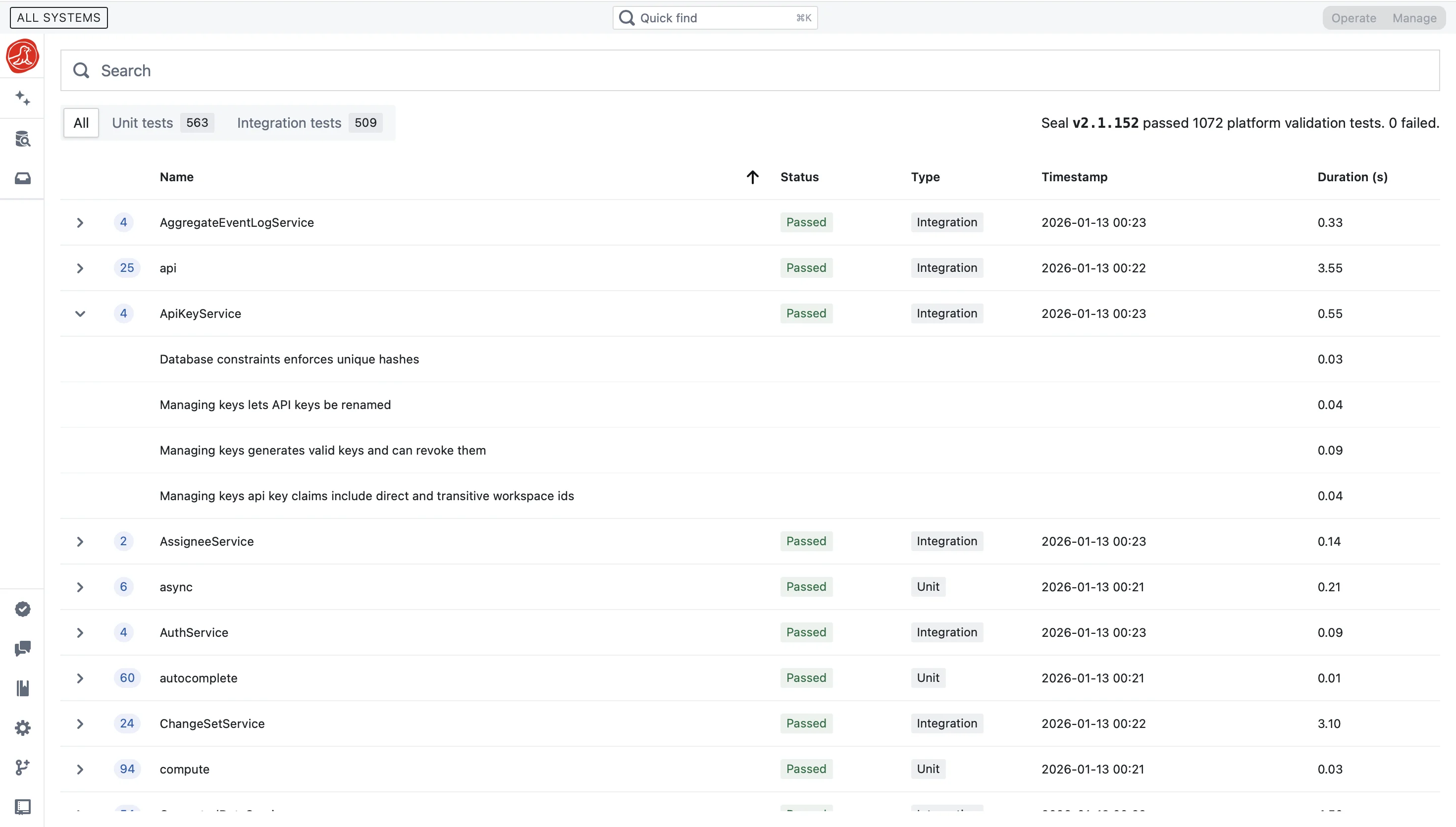

PPQ closes in weeks, not months. CPV reporting in days, not weeks. Teams of five doing what teams of sixteen used to do—because the assembly disappears.

The PPQ that took six months to close

Three PPQ batches. August to October. Every parameter in range. Every specification met. The process worked.

The validation report wasn't approved until February.

Not because anything failed. Because closing required assembling data from five systems—batch records from MES, test results from LIMS, environmental data from EMS, equipment logs from the historian, training records from HR. Export. Format. Compile. Reconcile. Verify. Cross-reference the deviations. Run statistics in JMP. Paste into the report template. Six months of documentation work to close a validation that proved the process worked in two weeks.

One company reduced their CPV reporting from two weeks to three days. Their CPV team went from sixteen people to five. Not through heroic effort—through eliminating the assembly.

PPQ with process and quality data together

Process validation answers one question: does the process consistently produce product meeting specifications? Answering requires two kinds of data—what happened during manufacturing, and what came out. In most organizations, these live in different systems. MES captures process parameters. LIMS captures quality attributes. To validate, you export from both, align by batch, and pray the timestamps match.

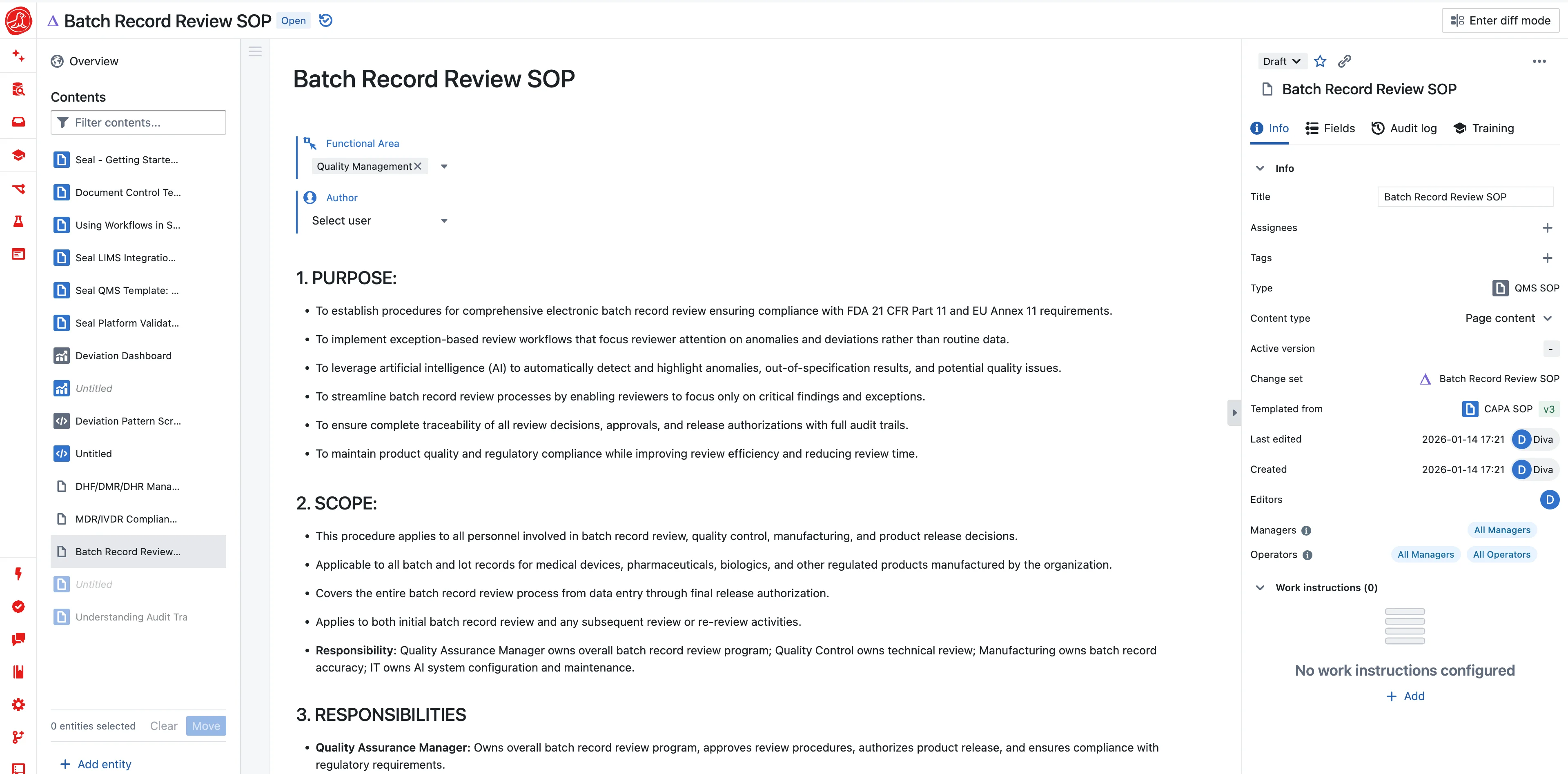

Seal keeps process data and quality data in one system. CPPs captured during manufacturing are already linked to CQAs measured during testing. Statistical analysis doesn't require export and alignment—the relationship between process and quality is the architecture.

Most validation protocols describe what will happen. Manufacturing runs the batches. Then someone documents what happened against what the protocol said. Retrospective. After the fact. Weeks later. Seal executes validation prospectively. The protocol defines acceptance criteria. PPQ batches execute against those criteria in real time. When a parameter approaches its acceptance limit, you know immediately. When a CQA result raises questions, the process data is already linked.

Validation requires statistics—Cpk, Ppk, control charts, confidence intervals. Most organizations run these in JMP or Excel, then paste outputs into reports. Seal calculates statistics on live data. The Cpk for temperature comes from actual readings captured during manufacturing. Change the data, the statistic updates. Question the statistic, trace it to the source.

CPV that actually continues

Stage 3—continued process verification—is supposed to be ongoing. In practice, most CPV programs are periodic reviews that happen when someone remembers, using whatever data they can easily export.

Seal makes CPV continuous because the data is already flowing. The same CPPs monitored during PPQ continue through commercial production. The same statistical analyses run continuously. When performance drifts—before it exceeds limits—the trend is visible. CPV isn't a quarterly exercise. It's a continuous state of knowledge.

Decision trees automate what experienced engineers do intuitively. Three consecutive points trending upward? Notify process engineering. Cpk drops below 1.33? Escalate to quality. Western Electric rule triggers? Flag for investigation. The rules execute continuously against live data. Signals surface immediately—not buried in a report nobody reads until there's a problem.

Two weeks per product for CPV reporting used to be normal. Export from MES. Pull from LIMS. Align in Excel. Statistics in JMP. Format in PowerPoint. With Seal, days—because the assembly disappears. Data flows continuously into statistical models. Control charts update in real time. When it's time for a periodic report, the content already exists. Review and approve—don't assemble and calculate.

Knowledge that compounds

CPV data has value beyond compliance. Every batch teaches you something. But knowledge fragments across systems, reports, and the memories of experienced engineers who eventually leave.

Seal builds an enterprisewide knowledge base from CPV data. Compare performance across lines. See how Site A differs from Site B. Track capability evolution over five years. "Has this ever happened before?" is a query, not a question for the person who's been here longest.

Process validation doesn't exist in isolation. The CPPs you're validating were established during characterization. The ranges you're proving were defined in your design space. Seal maintains those connections—CPPs link to characterization studies, acceptance criteria link to design space boundaries. When PPQ fails, you see how that parameter behaved during characterization, development runs at similar conditions, whether this is a new failure mode or a known risk that materialized.

Before PPQ, verify readiness—equipment qualified, personnel trained, methods validated, raw materials released. Most organizations use a checklist that's stale the moment it's signed. Seal checks readiness from live data. Bioreactor qualified? Query the equipment system. Analysts trained? Query training. If something changes between readiness verification and PPQ execution, you know.

Capabilities