Audit Readiness

Ask. Find. Show.

Auditors ask, you answer—in seconds. Pre-assembled packages, instant document retrieval, complete audit trails. Ready before they arrive.

"Can you show me the batch record for lot 2024-0847?"

The auditor asks. Someone leaves the room. Twenty minutes later, they return with a printout—hoping it's the right version, hoping nothing is missing, hoping the signatures are legible.

This scene repeats dozens of times per audit. Each retrieval is a delay. Each delay is an opportunity for the auditor to wonder what you're hiding. Each delay is a minute they're not reviewing your actual quality—they're waiting for you to find your own records.

FDA inspectors ask 30-50 questions per day. At twenty minutes per retrieval, that's 10+ hours of hunting. Two days of a four-day inspection spent watching your team search for documents.

The most damaging audit findings aren't about quality failures. They're about not being able to demonstrate your quality. "Records not readily available." "Unable to retrieve requested documentation." "Evidence of [thing you actually did] could not be located."

You did the work. You have the records. You just can't find them fast enough to prove it.

Instant retrieval changes everything

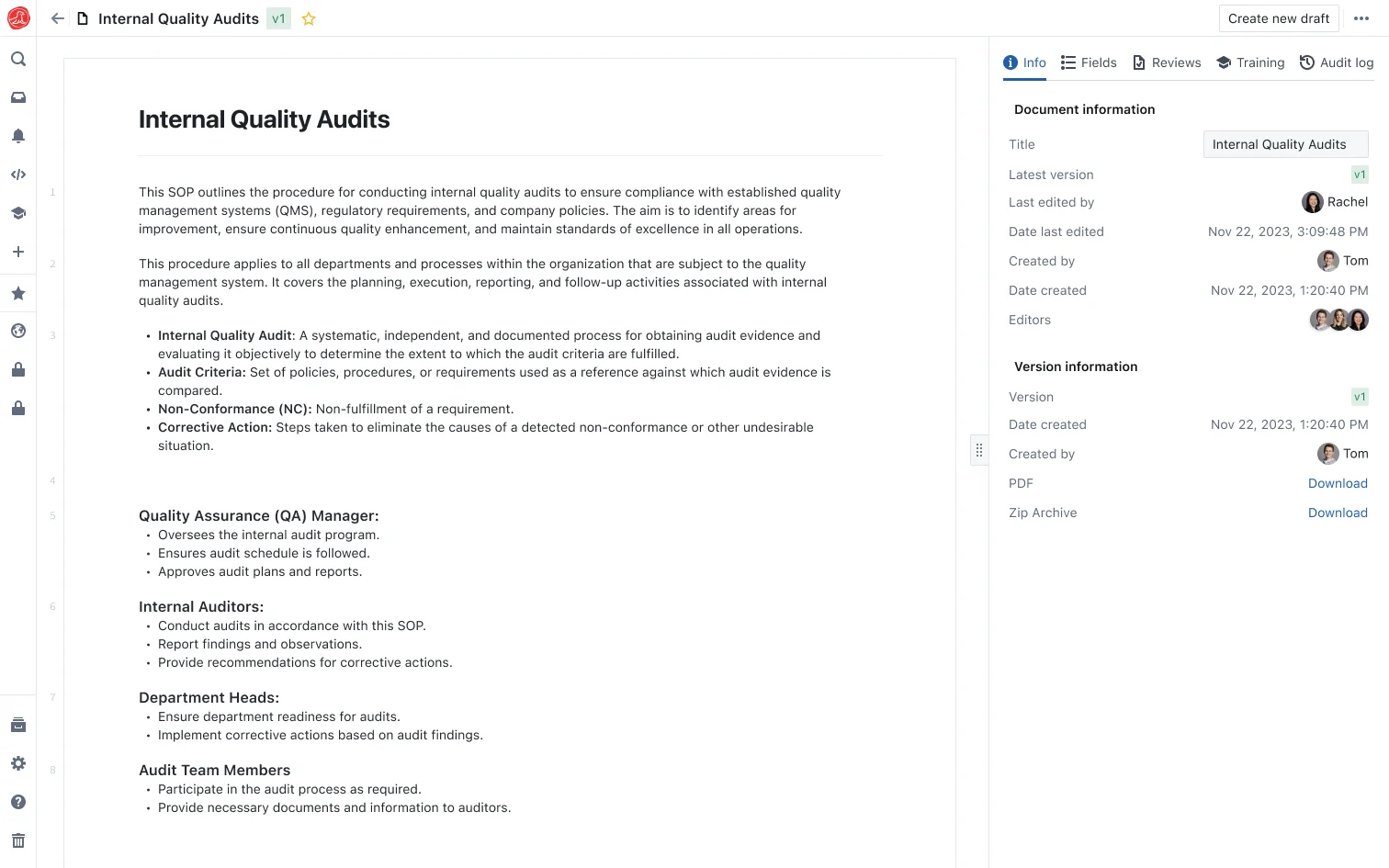

In Seal, the answer to "show me batch record 2024-0847" is a search, a click, and the complete record on screen. Every step, every signature, every deviation, every test result—linked and visible. Five seconds, not twenty minutes.

The auditor asks, you show. They want to see the deviation? Click. The CAPA? Click. The training record of the analyst who ran the OOS test? Click. The calibration status of the balance used in step 4? Already on screen, linked to the batch record.

No hunting. No waiting. No uncertainty about whether you found the right document. No wondering if there's a newer version somewhere else. No "let me check with Katie, she manages that spreadsheet."

The speed itself communicates something. An organization that can retrieve any record in seconds is an organization that knows where its data is. An organization that takes twenty minutes is an organization that might not know what else it can't find.

Pre-assembled audit packages

You know what auditors ask for. You've been through inspections before. Training records for personnel who worked on the batch. Equipment qualification for instruments used. Deviation history for the product line. CAPA effectiveness evidence. Environmental monitoring during manufacturing.

Why wait for them to ask?

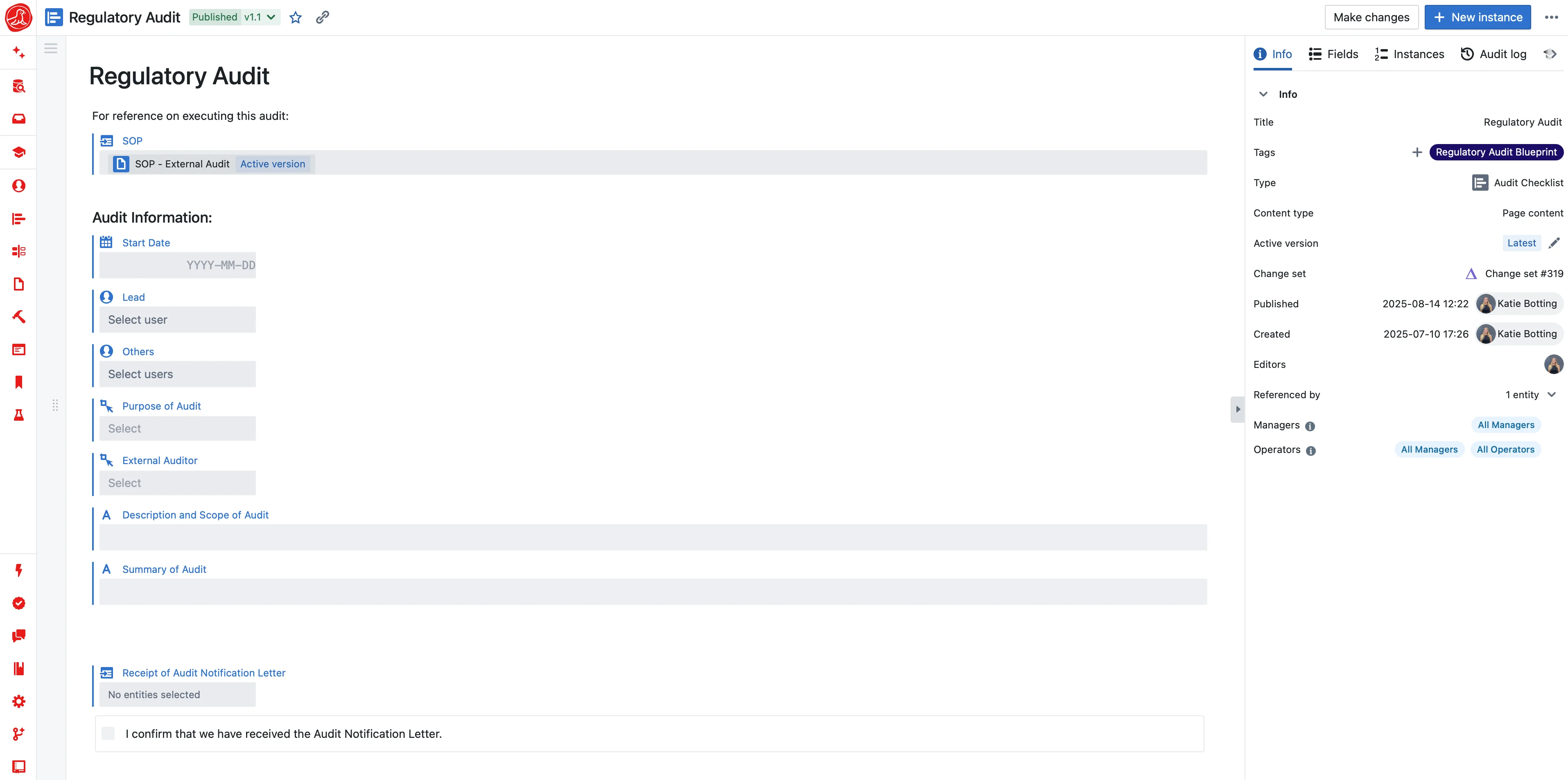

Seal assembles audit packages before the inspection starts. Define what records should be included for a given scope—batch documentation, product history, system overview—and the system pulls current data into ready-to-present packages.

The key insight: packages are defined by scope, not by static document lists. "All documentation related to batch 2024-0847" isn't a list of 47 specific documents. It's a query that returns whatever documentation exists for that batch. Deviation added yesterday? It's in today's package. Equipment recalibrated this morning? The new certificate appears.

When the auditor asks, the package is already waiting. Not because someone spent last week assembling it—because the system assembled it from live data this morning.

Complete audit trails that tell the story

"Who approved this change? When? What was the previous value?"

In paper systems, answering this requires finding the original document, finding the change control form, finding the approval signatures, and hoping they're all consistent. In most electronic systems, audit trails exist but live in separate log files that require cross-referencing with the actual records.

In Seal, the audit trail is attached to the record. Click "Show History" and see every modification, every approval, every signature with timestamp and user identity. Not a summary—the actual changes. The previous value was 100°C. At 2:47 PM on March 15, J. Smith changed it to 105°C. The change control reference is CC-2024-0234. Click to see the change control.

Auditors don't have to trust your summary. They don't have to wait for you to correlate log files. They can see the evidence directly, drill into any linked record, and verify for themselves.

Point-in-time verification

"Was this analyst qualified to perform this test when they performed it?"

This question sounds simple. It isn't. Current training status is easy—look up the person, see their qualifications. Historical status requires reconstructing what their training looked like on a specific past date.

In most systems, this means searching training records, finding completion dates, determining what was required at the time, and constructing an answer. "I think so" isn't good enough. "Let me get back to you" isn't good enough.

Seal maintains point-in-time training status. Ask "was J. Smith qualified for HPLC-001 on March 15?" and the system reconstructs their qualification status as of that date. Yes, they completed training on February 28. Their qualification was valid through June 30. On March 15, they were qualified. Here's the training record, the assessment, the supervisor approval—all as they existed on that date.

Same principle for equipment. "Was this balance calibrated when it was used for this dispense?" The balance used for lot 2024-0847, step 3, was calibrated on February 1, due for recalibration April 1, used on March 15. Calibration was current. Here's the certificate. The auditor doesn't have to do the math—the system already knows whether calibration was current at time of use.

Deviation and CAPA effectiveness

Auditors don't just want to see that you closed deviations. They want to see that your corrective actions actually worked. "Show me that this CAPA was effective" is the question that separates organizations that fix problems from organizations that close tickets.

Seal links the complete chain: deviation → investigation → root cause → CAPA → corrective action → effectiveness verification → monitoring data. "Show me deviations for this product line" returns not just deviation records, but the corrective actions taken, the evidence that actions were implemented, and the data showing whether recurrence was prevented.

When an auditor asks "how do you know this CAPA was effective?" you don't explain your process. You show them the effectiveness check record, linked to the monitoring data that demonstrates recurrence prevention, linked to the original deviation that started the chain. The evidence speaks.

Natural language search across everything

Not every question maps to a specific record type. "Show me everything related to the contamination event last quarter." "What do you have on temperature excursions in Building B?" "Pull together the history on this supplier quality issue."

Seal's search understands context. "Contamination event last quarter" isn't a record type—it's a concept that spans multiple systems. The search finds the deviation, the investigation, the affected batches, the CAPA, the environmental monitoring data, the personnel training updates, the equipment cleaning records, the supplier communication—everything connected to that event.

This isn't keyword matching. It's semantic understanding. The system knows that a "contamination event" might be called a "microbial excursion" in environmental monitoring and an "OOS investigation" in QC and a "sterility failure" in the deviation system. It finds all of them.

Mock audit mode

Run mock audits before real ones. The best preparation for an inspection is simulating one.

Seal tracks common auditor requests—the questions that come up in every inspection. Mock audit mode lets you simulate the experience: random questions, timed retrievals, scored responses. Find gaps in documentation before the auditor does. Identify slow retrievals before they become audit observations. Practice the workflow so your team responds confidently.

You can also run targeted simulations. "If an auditor asked about our sterility assurance program, what would we show them?" Generate the package, review for completeness, identify gaps while there's still time to address them.

Practice doesn't make perfect. But it does prevent the embarrassment of fumbling for basic records in front of regulators.

The inspection that felt like a conversation

When retrieval is instant, the inspection dynamic changes. Instead of waiting for documents, auditors spend time actually reviewing your quality system. Instead of wondering what's missing, they can follow any thread to its conclusion. Instead of asking for records, they can ask about decisions—why you chose this approach, how you evaluated this risk, what you learned from that deviation.

These are better conversations. They demonstrate that you understand your own quality system, not just that you can find your paperwork. They give auditors confidence that your documentation reflects reality, not just that you documented extensively.

The best audits don't feel like interrogations. They feel like quality reviews with a knowledgeable external partner. That only happens when retrieval isn't the bottleneck.

Capabilities